P.D. Soros Fellowship for New Americans

If you are an applicant and need to sign into the online application, you can find the link on the "Apply" page of our website: Apply Page.

If you are a fellow looking to login, please note that we are currently updating our backend system for managing Fellow data. In the meantime, to update your information for the Fellowship, please send updates to Nikka Landau at nlandau@pdsoros.org.

A Belated Goodbye

By Irina Linetskaya

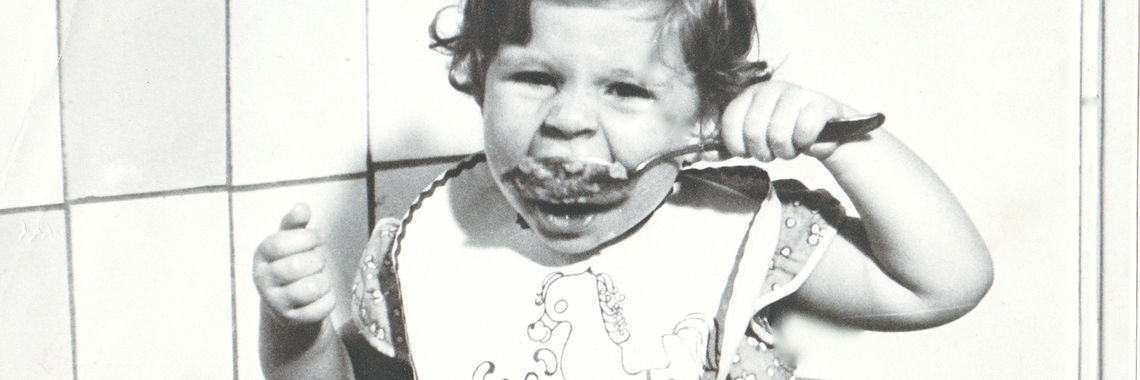

In 1977, the excitement over my birth was overshadowed by the thrilling news that my family had gotten permission to immigrate to the United States. Along with thousands of Jewish refugees, my family sought asylum from the long-standing anti-Semitism of the Soviet Union. However, only weeks before our scheduled departure, the borders of the USSR closed. We would be trapped in the country for the ensuing 11 years—years that upended my family’s structure and destiny. In 1979, when I was two, my father died suddenly at age 45 of cancer, or a brain aneurysm, they said, unsure.

Then, in I986, the nuclear reactor in Chernobyl exploded 60 miles outside our home in Kiev, Ukraine. Because the government covered up the accident, we continued to expose ourselves to radiation through water, milk, and food. In 1987, shortly after the catastrophe, my mother died at the age of 40. I turned 10 that summer. Through it all, my family continued to face unremitting discrimination.

Being Jewish in the Soviet Union was a tremendous burden, one that had marked my family’s fate for generations. Although both of my grandparents survived the Holocaust, anti-Semitism persisted undiminished long after World War II. Even during my childhood, the persecution of Jews was widespread and state-enforced. It began at birth, when each citizen’s nationality was stamped in his or her passport. A Ukrainian’s passport read “Ukrainian”; a Georgian’s said “Georgian.” But a Jew’s passport, regardless of the republic of his or her birth, was always stamped “Jew.” This branding allowed the state to bar Jews from social advancement, higher education and desirable jobs. In fact, both my mother and her brother, top graduates of their respective high school classes, were rejected by Kiev’s Polytechnic University and forced to get their engineering degrees through correspondence courses in Moscow and Siberia.However, because communism abolished the fundamental concept of religion, we were not practicing Jews. In fact, I don’t recall ever being introduced to the concept of God or spirituality. “Jewish” was an ethnic marker, not a religious one. But unlike the rest of my family and community, I was born with an uncanny gift: a shikse punim, meaning a gentile girl’s face, as Jewish elders commented, often surprised that I was actually Jewish. My blond hair and goyishe features allowed me to slip under society’s anti-Semitic radar unnoticed.

A hilarious shot of Grandma (looking fierce), my brother Leo (aka Rambo) and me in 1987 looking like some kind of touring circus acrobat troupe.

Photo of me age 5 or so grinning like a fool despite the massive Soviet bow threatening to crush me from above.

After my father’s death, my mother changed my unmistakably Jewish last name of Vieselman to her less conspicuous one, Linetskaya, a brilliant precaution that further assured my “passing.” So while other openly Jewish children, including my much older brother and classmates, were bullied, harassed and ostracized at school, I enjoyed relative popularity. I was simultaneously guilty and

triumphant, motivated by their suffering to defend my secret at all costs.

My Jewish identity felt like a haphazard and confusing shadow lurking behind me. When children taunted each other, the word zhid (a particularly caustic anti-Semitic slur) was a crowd favorite, an insult aimed casually in all directions. At the sound of the word, my senses would sizzle to life as I waited for the insult to be aimed at me and stick. But it never did. No one, it seemed, suspected a thing.

Hiding such a fundamental element of my identity also meant that I couldn’t invite friends to my house. The most subtle clues could give my family away. And nothing about my family was remotely subtle. Our home, too, trembled under the strain of anti-Semitism. After my father’s death, Mama married a non-Jewish man who turned out to be violent and erratic, often battering my brother and mother while screaming “you dirty Jews!” When not trying to place my little body between his fists and my mother’s body, I would hide in the corner, trying desperately to escape into the tales in my

yellow Hans Christian Andersen book, wishing this “Jew” word would stop poisoning my life.

On weekends and school holidays, I escaped to my grandparents’ house, a safe, warm apartment on the other side of the city. But I couldn’t risk inviting friends there either, as my grandparents’ constant bickering in Yiddish would surely spoil my disguise. So I made up endless excuses and kept my friends away from my family.

One day, on our walk home from school, Sveta, my best friend, asked me what my grandmother’s

name was. “Fanya,” I casually replied. “Fanya? Hmm…but Fanya is a Jewish name,” she slowly

replied, suspicious in her 8-year-old knowing. I froze, petrified, panic thrumming in my ears. You sloppy idiot, I berated myself while spinning impromptu lies, terrified that my one thoughtless blurt, the two innocent syllables of my grandmother’s name, had sabotaged my impeccably constructed facade. But how did she know? Did Sveta’s family recite lists of Jewish names at the dinner table? Opting for the snooty tack, I quickly retorted: “Anya, not Fanya, you nimrod! Why would my Grandma’s name be Fanya?” She shrugged and seamlessly moved on to a new topic. But I trembled for days to follow, nerves on edge, and watched my friend carefully for signs of suspicion or malice. I increased my vigilance, and although nothing dreadful came of this incident, the Jewish shadow behind me became grayer and more ominous. Of course, I instinctively knew that my careful lies, my decoy last name and my shikse punim were only temporary camouflage; the “Jew” stamped on my passport would eventually surface, topple my life and truncate my future.

When my mother died shortly after my tenth birthday, the Soviet government began legal

proceedings to place me in a state-run orphanage. At 67, Grandma struggled with Parkinson’s and rheumatic heart disease and was deemed too frail to take care of me. Grandpa, 11 years her senior, once a robust man with a rotund belly and teenager’s stamina, was losing weight at an alarming rate, an early sign of his gastric cancer. But Grandma, the most tenacious, principled person I have ever

known, fought tirelessly to become my legal guardian. She persevered, and her guardianship changed the course of my life forever. The very next year, when Soviet borders finally reopened to Jewish emigration, my grandparents did not hesitate. Despite their advanced age and deteriorating health, they uprooted themselves, their lives, and their belongings in order to give my life a chance in America.

Leaving was bittersweet. Sure, I was mildly piqued by the promise of “freedom” and “opportunity” the adults seemed to be abuzz about (although I was ecstatic about the prospect of real, fresh bananas!). But I dreaded leaving my friends, the games we played on the Kiev streets until all hours of the night, the time capsules we buried in the park before snowfall, the universe of make-believe

and laughter that had buffered my otherwise turbulent reality. And yet, on the chilly November morning in I988 when we left Kiev forever, I didn’t say good-bye to any of my friends. Not even Sveta. I was too ashamed to admit that I had deceived them all along, that the very identity I had hidden so carefully from the world was now my family’s ticket out of the Soviet Union.

My grandparents, my uncle, and I stuffed ourselves and our possessions into a taxi and embarked on a grueling year-long journey to America. I barely recall the interminable train rides from Kiev to Moscow to Vienna and Rome, hopping from one refugee settlement to another as we appealed to our final destination countries (Israel, the US, Canada, Australia, and Germany) for asylum. Finally, after 10 months of anxious waiting, we learned that we were going to be sponsored by Grandma’s sister, who lived in California. I distinctly recall that Pan Am flight from Rome to New York, my first ever. We arrived in Oakland on September 20, 1989.

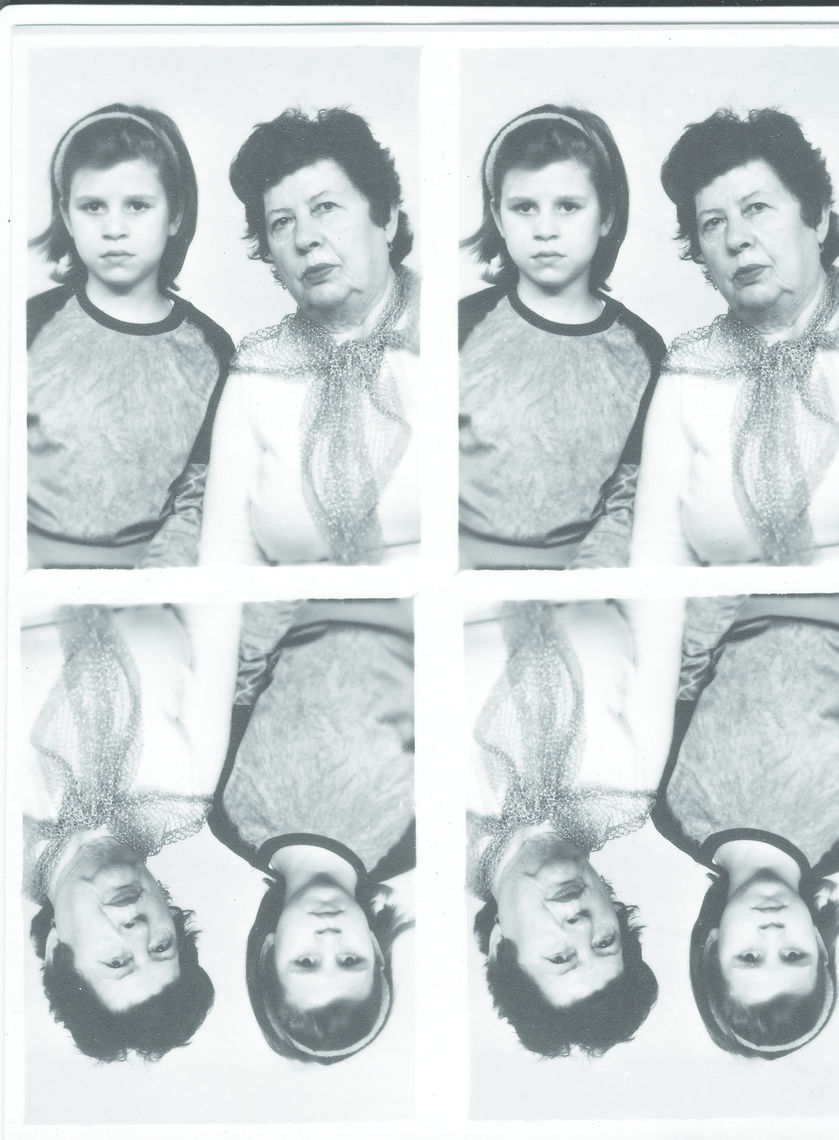

The joint passport photo of my grandma and me was on my visa to exit the Soviet Union.

A treasured shot of me and Grandma on her 90th birthday in 2012 (three months before she passed).

During our first year in America, my grandfather lost his agonizing battle with stomach cancer, my uncle got married, and my Grandma and I—at 67 and I2—became a fierce battalion of two. The culture shock of the United States was bewildering and exhilarating. In comparison to the turmoil, loss, and fear that had enveloped my childhood in Kiev, my new life was relatively peaceful. I thrived in school, absorbed English in gulps, made new friends. After a year of ESL classes, brandishing my accent-free California girl English, I was seamlessly integrated into mainstream classes with American kids. But with new friends came the task of explaining how my family had made its way to America, and why. My relentless chattiness would halt when faced with such questions. “We came for a better life,” I would hedge, mortified by the prospect of going deeper, of admitting that I was Jewish. I vividly recall the first time I managed to get the sticky words out, words that had been shackled to my vocal cords by years of hypervigilant secrecy. “We came because we are...we are...because we are Jewish,” I blurted out to Faedra, a gregarious classmate with wild curly hair and curious gray eyes, and froze, waiting for the cataclysm.

In my twelve years, I had lost innumerable loved ones, crossed an ocean and learned a new language, yet uttering that sentence felt insurmountable. I had never confided to anyone that I was Jewish. But

Faedra merely shrugged and replied, nonchalantly, “So what? I’m Jewish, too. What’s that got to do with anything?” So what? Indeed.

In retrospect, I realize that this brief exchange marked a transitional point in my life, a point when fear and shame gave way to the seeds of self-awareness and liberation. Gradually, I found that I could admit I was Jewish without choking on the words. Eventually, “admitting” began to feel like “telling,” and later still, the whole subject became second nature.

Once I felt firmly settled into my integrated identity, nearly two years after arriving in the U.S., I painstakingly drafted a belated goodbye letter to Sveta in Kiev. I recall few details about Sveta’s reply or our brief letter exchange. But I do remember writing and rewriting my letter until I got the wording just right. Finally, in meticulous cursive, using my beloved purple pen, I wrote a sincere apology to Sveta for vanishing without a word. I apologized for deceiving her about my being Jewish, admitting that I had felt ashamed of it and was scared that she wouldn’t be friends with me had she known. I explained that we were in America now and that I was doing well in school. I

folded the letter with trembling hands and stuffed it into a plain white envelope. Yet the

letter felt much heftier in my hand than the single piece of paper it contained.

Perhaps the remaining dregs of shame and secrecy had tucked themselves into the folds of paper, returning to their hatching place in the former Soviet Union. They were no longer part of me in America.

-

A photo of my mom with me (left), my brother (middle), and a neighbor (right) circa 1979.

© 2024