P.D. Soros Fellowship for New Americans

If you are an applicant and need to sign into the online application, you can find the link on the "Apply" page of our website: Apply Page.

If you are a fellow looking to login, please note that we are currently updating our backend system for managing Fellow data. In the meantime, to update your information for the Fellowship, please send updates to Nikka Landau at nlandau@pdsoros.org.

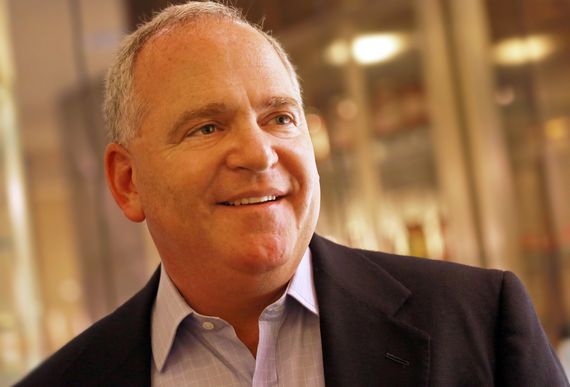

Meet Ken Buckfire

-

Photo Credit: Kathleen Galligan, Detroit Free Press, ZUMA.

Photo Credit: Kathleen Galligan, Detroit Free Press, ZUMA.

Kenneth (Ken) Buckfire is one of the two new board members of the Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowships for New Americans.

Like many Fellows, Ken has led an incredibly successful career spanning both the public and private sectors. Currently, he is the co-president of Miller Buckfire, a New York-based firm focused on financial restructuring. There, Ken has advised clients in a wide range of industries, including companies in the energy, food products, building products, and broadcasting sectors, among others.

Yet, as a Detroit native, I heard of Ken through not his corporate restructuring work, but rather his public sector restructuring work. From 2012 through 2014, Ken worked tirelessly—and successfully—to shepherd my hometown through Chapter 9 bankruptcy, the largest municipal bankruptcy in US history. Of import, Detroit is also home for Ken, a fact that drove his decision to take on the assignment.

In parallel to his restructuring work, Ken has also been deeply involved with leading philanthropic organizations, including the Zell-Lurie Institute, the Philharmonic Symphony Society of New York, the Weill Cornell Medical Dean’s Council, and—as of this Spring—this Fellowship.

He received his MBA from Columbia University and his BA in economics and philosophy from the University of Michigan.

You’re an old friend of Paul and Daisy.

That’s right.

How did you come to know them?

Paul and Daisy were my neighbors in Nantucket. We first met there.

I understand you had a deep relationship with Paul in particular.

Paul was a remarkable guy. He was brilliant, kind, and insightful. He also had no illusions about the way the world works. He sincerely believed that had been given so much by the United States, and that he had an obligation to provide the same opportunities to others.

What do you think the Fellowship meant to Paul?

When Paul came to America, he had nothing. Actually, less than nothing. The Fellowship was more important to him than almost anything else he did. He did a tremendous amount for the world through the world as a professional, but, again, he felt he had an obligation to do whatever he did for the US.

Given your leadership in both the private and public sectors, it seems that you have had a similar view.

Yes. The United States is a unique place. Being an American is about accepting the obligation to give back. That was the one thing that made the US unlike any other place—that sense of charity, generosity, and social obligation.

What does serving on the Board mean for you?

The board had meant so much for Paul. I want to keep that relationship going. I’m here to help Daisy and the others carry out Paul’s legacy. That’s what serving on the board means to me.

Any specific ideas that you would like to see implemented?

Paul wanted to have as deep a reach into the cadre on the New Americans as possible. I would like to see the Fellowship be aware across the country, especially outside of the coasts. There are many more talented deserving people who could make good use out of the Fellowship.

Tell me about your immigration story.

My family came from Europe. My family came over under very difficult circumstances. My grandparents were refugees. I’m a generation-and-a-half American. We’re all very grateful. I feel very indebted to the US for what they’ve done for my grandfather and everyone else.

What lessons did you learn from your grandparents and parents?

I was raised from the early days that it’s extremely important to make the world a better place. There’s an old Jewish principle that you ought to make the world better every day, and I chose to do that through my work in restructuring.

Did this factor into your decision to work for Detroit?

When the opportunity came up to help restructure Detroit, I felt very good about it. It was an incredibly difficult assignment, but I am glad that we got to go back home and do that something like that. I believe in the principle that “if your work isn’t making the world a better place, find something else to do." More broadly, it’s one of the reasons to do what do what I chose to do. We do restructuring because we can really make a difference.

What have you learned from your public sector restructuring work generally?

It’s easier now to do public-private work than 20 years ago. People in both sectors have a much greater sense of mutual appreciation. You have many examples these days of how the application of public sector thinking has actually worked out. You are seeing, for instance, people in the private sector looking at well-run public sector enterprises. It’s not true, and it’s never been true that the public sector has been inherently inefficient.

I agree, though it’s not often you hear someone from the private sector praise the public sector.

Most governments are actually run very efficiently. They deliver value for the money invested. If you look at the Tennessee Valley Authority, for instance, they do a great job. Many companies in the private sector likely couldn’t do that. There’s many other examples. Generally speaking, management principles are very universal. Good managers can lead effective organizations in both the public and private sectors.

You’ve led an equally impressive philanthropic career, serving on the boards of a number of major nonprofit organizations.

Paul figured this out a long time ago. Philanthropy is extremely important. Particularly in case where there is a measurable impact and the underlying objective is missioned-best—whether, for instance, it’s focusing on the medical research or high priority issues or bringing world-class classical music into the reach of more people—you can really have a huge impact. My wife and I, for instance, have also funded the summer honors program at the University of Michigan. It’s totally measurable in terms of the impact on the students’ careers—and the impact has been significant.

If I remember correctly, the honors program focuses on interdisciplinarity. You majored in an interdisciplinary concentration in college: economics and philosophy. The Fellows have also historically come from a diverse array of intellectual disciplines.

We live in a complex world, and we have to be nimble thinkers capable of looking outside our immediate worldviews. The Fellows’ diversity of backgrounds speaks to the Fellowship’s real strength in bringing people with interesting backgrounds. The fact that the Fellowship looks for mathematicians, musicians, and writers is great. You can’t look at the world anymore and believe that it’s understandable from one intellectual prism, and it’s great that the Fellowship recognizes this.

Many of our Fellows are graduating in the near future, what sort of advice would you give to them as they are thinking through their future career options?

I think the only advice I’d give is the only advice I’d give my children. Work is really important. Pick something because it has the greatest positive impact on the world, where it also gives you the greatest number of options for what comes later. Don’t take something which is not terribly useful to other people and fails to give you more options.

Interview by Richard Tao (2014), senior advisor to the mayor of Detroit.

© 2024