P.D. Soros Fellowship for New Americans

If you are an applicant and need to sign into the online application, you can find the link on the "Apply" page of our website: Apply Page.

If you are a fellow looking to login, please note that we are currently updating our backend system for managing Fellow data. In the meantime, to update your information for the Fellowship, please send updates to Nikka Landau at nlandau@pdsoros.org.

She's In The Fight, Always

When Pardis Sabeti (2001) answered her cell phone, she didn’t stop Rollerblading. And after nearly an hour of conversation, she was still on her skates and didn’t sound winded. Two things come to mind. First, you don’t want to try to keep up with this woman, on any level. Second, even on a recreational break from her teaching and research at Harvard, she’s multitasking. She’s a scientist of the moment, someone who has spent the last year battling Ebola in Africa and is now helping to design new techniques for data mining, as a spin-off from her groundbreaking work in genetics.

While she skates, to the sound of lawns being mowed along her path, she traces the success of her career—one is tempted to call it a destiny, given its drama and brushes with tragedy. She talks of three crucial turning points. The first was when she got her first glimpse of her future as a sixth-grader in Florida. A film she watched in her advanced math class showed students operating autonomous robots they had designed and built for the annual 2.70 (now 6.270) Competition sponsored by MIT. She thought, “That is the coolest place on earth. That’s where I want to live.” So she did, getting her undergraduate degree there a decade later. In a sense, she’s still living in that world. Right now, she works only a few miles away from that school, at Harvard, where she teaches genetics and devotes herself to both basic and applied scientific research.

Looking back, after the first decade of a pioneering career, she can identify two other pivotal moments. When a car accident shattered her father’s legs, Pardis, only in her teens, convinced the doctor who operated on him to let her be his apprentice. That’s when her love for science narrowed into a love for medicine. The third pivot in her life was the day she won a Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowship. It gave her the time and freedom to completely immerse herself in genetic research, and it led to a fundamental discovery about how to identify and analyze the most recent genetic mutations governing human immunity to disease. The Fellowship essentially gave her the courage and freedom to stay up until 3 a.m. chasing and finding something no one else knew. What she discovered became a routine tool researchers use to recognize significant needles in the haystack of data encoded into a genome.

She told PBS the exhilaration of that moment is what continues to drive her forward in life: “It’s the thrill of discovery. It’s a wonderful, wonderful scavenger hunt, when you get to the end.”

Her breakthrough in those wee hours, poring over data, continues to open doors. The media flocks to her. She has been profiled by NOVA and Smithsonian and Time magazines. She has won six- and seven-figure grants for her work from the National Institutes of Health, Gates Foundation, Packard Foundation, and, most recently, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, one of the most prestigious in science. She was among the Ebola fighters in Africa named as Time’s Person of the Year in 2014. This year, Time followed up by including her on its 100 Most Influential People list.

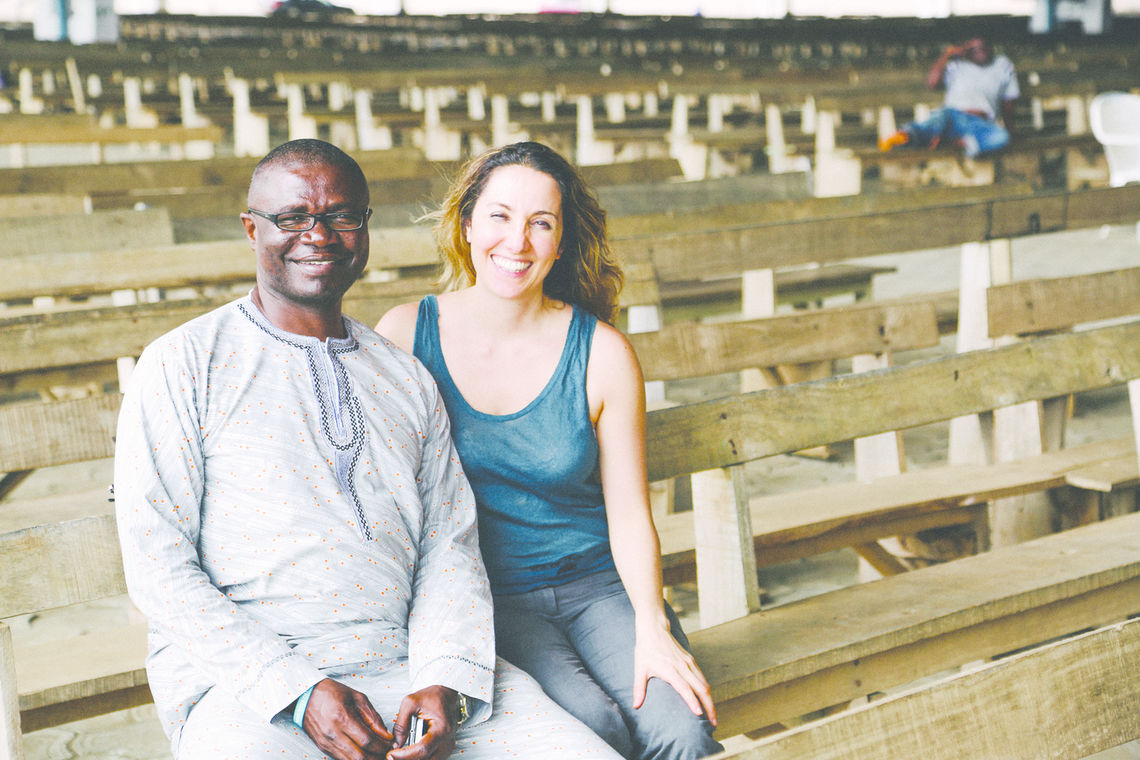

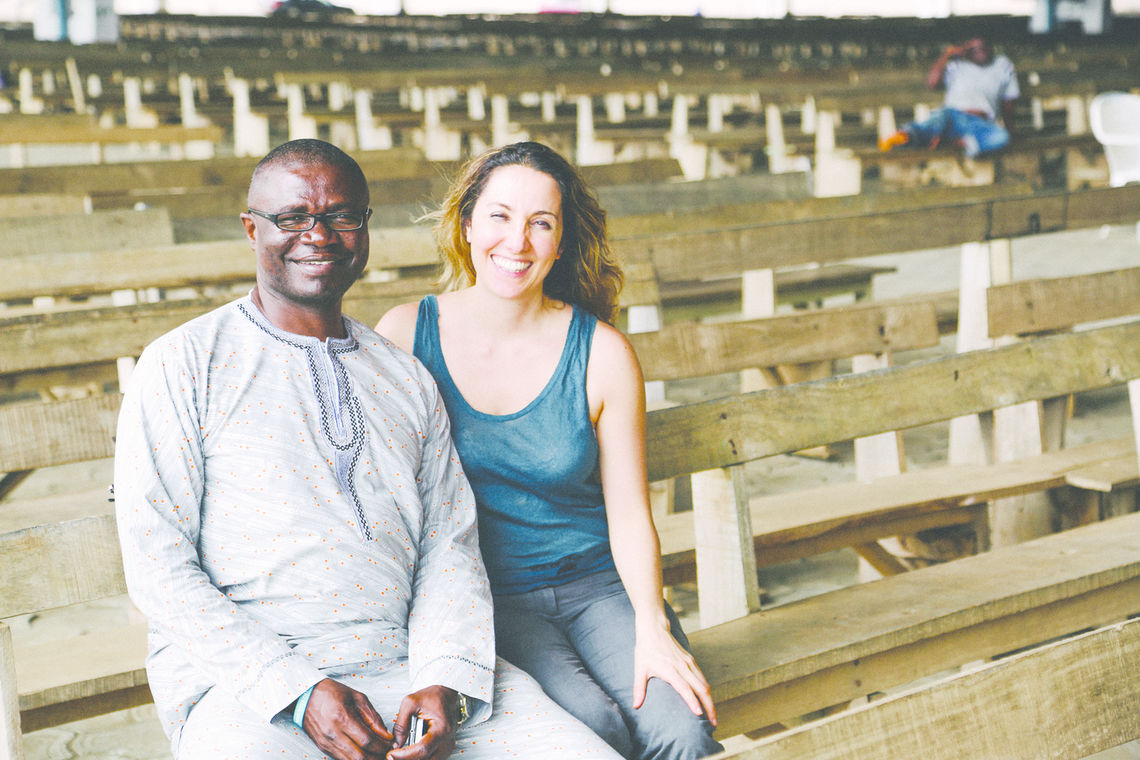

Pardis Sabeti with Christian Happi of Harvard University, 2013. Photo courtesy of Nathan Yozwiak.

Pardis at work in Sierra Leone, 2013. Photo courtesy of Erica Ollman Saphire.

Pardis Sabeti with Christian Happi of Harvard University, 2013. Photo courtesy of Nathan Yozwiak.

Essentially, if her work ever saves lives in an epidemic—and it undoubtedly already has—she believes the survivors will have The Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowships for New Americans to thank, along with everyone providing health care based on her research.

“My lab and I develop statistics that allow the genome to pinpoint the important mutations that occurred in human history. This led us to Lassa fever. Lassa is on the list of emerging diseases, but we found a signal that seemed to say it’s an ancient force. So we started questioning, Was this disease widespread and not being reported, and were people who carried a particular mutation in the genome resistant to Lassa fever? That’s how I got to Africa. That test told me this is a disease we should pay attention to. We’ve been studying Lassa fever for seven or eight years and are only now beginning to publish original research, but we have had important insights along the way, like the hypothesis that socalled emerging diseases like Ebola and Lassa fever are not new diseases but just new detections of diseases that have been here for millennia, that they may have long been circulating undetected.”

Science published their perspective, “Emerging Disease or Diagnosis?” in 2012, years before the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The same journal also published a paper she and her collaborators wrote about how to analyze large data sets for useful information. It described a new statistical approach to detect patterns of any kind in any large collection of data.

“In the past, we had only certain ways to explore associations in large data sets. I worked together with two brilliant young students who developed mine [Maximal Information-based Nonparametric Exploration], a powerful new way to find many relationships in the data.” In an accompanying piece published in Science, the new test was said to be a “culmination of more than 50 years of development of [mutual information].” It has already been cited many hundreds of times, and the software to carry it out has been downloaded by tens of thousands of users.

This impactful piece of work is very much a PD Soros paper. It began almost accidentally. By happenstance, Pardis had met Dave and Yakir Reshef, now both PD Soros Fellows, and they shared an interest in computation, science, and public health. They were trying to discover ways of finding patterns and significance in large amounts of data on public health, and later found its utility to so many data sets, from genomics to finance to even baseball.

Now with PD Soros support of their own, Dave and Yakir are getting that same freedom Pardis once enjoyed to pursue their passion, and have been expanding the theoretical and practical implications of mine much further.

-

Pardis Sabeti with Philomena Ehiane, 2013. Photo courtesy of Nathan Yozwiak.

Their work on data mining also has important applications to Ebola. Pardis and her team have gone on to find sophisticated ways to establish a person’s risk of dying and know what data points to collect. The most important single factor is an individual’s viral load: how much of the virus is active in the body. “Yet that alone isn’t so predictive, but when you use all the variables together, you can get to near 100 percent prediction accuracy.” Even with the gaps typical in data for public health, her research enables workers to extrapolate from what information is available to make accurate predictions. “We also created an Android app that will carry out the analysis and give you a predicted risk, by best taking into account the information you do and don’t have.”

The upshot of her research over the past decade is that she can see a way toward preventing outbreaks by being able to identify precisely where a particular virus is lurking—regardless of current symptoms. She recently proposed a program to do that with the Africa Center of Excellence in Genomics and Infectious Diseases. “If these viruses are circulating we can put in...an early-warning system for the next outbreak. We are a small group, and it took years to get funding, but we now have it.”

This work can be just as heroic as it sounds. And that comes with a cost. As thrilling as a 3 a.m. discovery of some basic truth can be, it led last year to work in Nigeria and Sierra Leone, where death was an immediate risk. Her life over the past couple of years has been exciting and fulfilling, but sobering and humbling. Ebola killed some of her close colleagues in Africa as they fought to defeat it. “If I could take back the past year, I would. We lost many colleagues, and the countries where we worked are devastated. There’s no way around it: we all lost a few decades of our lives in the process of this, and we experienced how chaotic the international front can be. It was not a good year by any stretch, but it was a meaningful one. It was a nightmare, but if it had to happen, it was fulfilling to be part of the response.”

Her work as a singer and songwriter merged with the fight against Ebola at a time when she needed it most. For many years, she had kept a tradition to always collaborate musically with the West African scientists who had fought disease alongside her on their many visits back and forth across the Atlantic. They promised to always keep at least a weekly appointment to do so no matter the circumstances. One song of hers rose up spontaneously from the crucible of their struggle as they learned about friends who had just died.

“Two of the nurses in our clinic in Sierra Leone had come down with Ebola. By the next weekend, they had both died, and the head physician had contracted Ebola. That Friday, my collaborator in Nigeria called and told me he had just diagnosed Ebola in Nigeria. In such a short span, people who had previously been healthy had died, and Ebola emerged in Nigeria. As we got together, I thought, ‘I don’t even know why we’re here, but we had always said whatever happens we will keep our promise to sing.’ We pulled out an old, unfinished track, with just a simple repeating chorus—uh, uh, uh, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah—and the girls started harmonizing, and before I knew it, words were coming out of my body and out into the world, and it became the song ‘One Truth’ that I was singing to my colleagues across the ocean to tell them, ‘I’m here in this fight [with you] always.’”

© 2024