P.D. Soros Fellowship for New Americans

If you are an applicant and need to sign into the online application, you can find the link on the "Apply" page of our website: Apply Page.

If you are a fellow looking to login, please note that we are currently updating our backend system for managing Fellow data. In the meantime, to update your information for the Fellowship, please send updates to Nikka Landau at nlandau@pdsoros.org.

Who is an American?

-

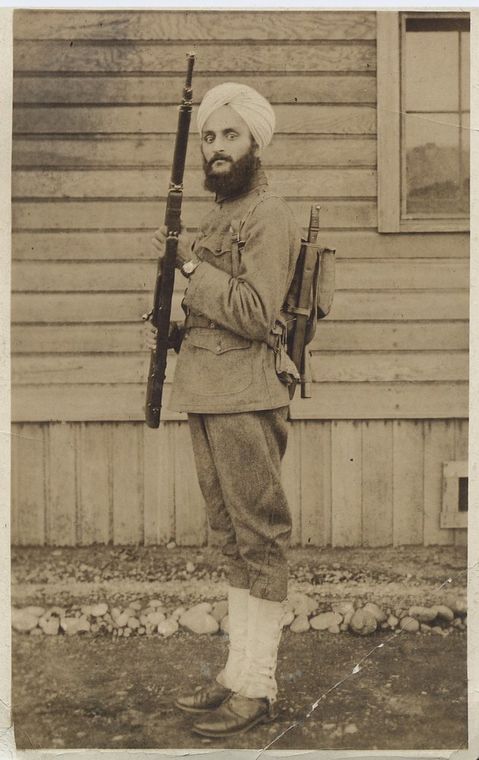

Courtesy of David Thind and the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA).

Nishant Batsha (2013 Fellow) is a writer and historian. He lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, where he is completing his PhD dissertation in history. He is also at work on his first novel.

The immigrant is often forced to yearn for legal recognition. This is a fact borne by an American history that includes the 1923 Supreme Court case United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, which concluded that all South Asians were ineligible for citizenship. In an age where presidential candidates openly question the Fourteenth Amendment, all may do well to remember the enduring struggle for citizenship.

The story begins like so many others: wanting a better life. Just twenty-one at the time, Bhaghat Singh Thind crossed the Indian Ocean to emigrate from Punjab in British India to Manila in the Philippines. From there, he took his journey across the Pacific to the western United States and reached Seattle on July 4th, 1913. He found his way to an Oregon lumber mill, and through splinter and sweat saved up enough money to enroll at the University of California, Berkeley to complete a doctorate.

One year later, the guns of the Great War sounded throughout Europe. And in April 1917 America entered the war. The image of American doughboys shipped off to Europe remains indelible: an olive-brown service cap closer to a cowboy’s hat than a general’s, a five-button khaki service wool coat, and a rifle slung over a shoulder. These were the sons of American soil, crossing the Atlantic to fight a war to end all wars.

In 1918, Thind heard the call to fight and was recruited into the army to join these soldiers overseas. He was issued a standard uniform. An image exists of him in a khaki wool coat, khaki pants, and service boots. Atop his head is not the familiar cowboy’s hat however, but a turban. His face was not doughboy-smooth, but instead with a full beard—insignias of his Sikh faith. He rose through the ranks to Acting Sergeant and was eventually honorably discharged.

Having fought for his country, Thind applied for American citizenship. His nationality was cataloged as Hindoo. It seems as if the Bureau of Naturalization ignored his Sikh faith and conflated a national origin with a religious background. His application was denied on the basis of the 1790 Naturalization Act. This law, passed in the cradle of a new nation, said that the right to become naturalized was reserved for “free white men” only. Perhaps the women and African slaves who too built this country were thought of as permanent guests. Undeterred by such logic, Thind applied for and was granted citizenship in Oregon. In this case, the local immigration judge threw legislation into the wind, and granted Thind citizenship on the basis of his service and his education.

The federal Bureau of Naturalization appealed and soon the case went to the Supreme Court. Forgetting that the master’s tools will not dismantle the master’s house, Thind’s lawyers made an argument that they thought would appeal to popular racial science and history: Thind should be considered “Caucasian” because he was a high-caste Indian of pure Aryan blood (using the fanciful idea that ancient India was settled by an invading race of Aryans).

The Court had earlier said Caucasian was synonymous with white. The case opened with a question: “Is a high-caste Hindu, of full Indian blood, born at Amritsar, Punjab, India, a white person?” Though the Court accepted the tale that Aryans and Caucasians had scattered themselves about the earth and made their way to India, the majority decision made an argument centered on recognition and passing. Would Bhagat Singh Thind be recognized in public as a Caucasian? Would he pass the more rigorous test of we know one when we see one? Justice Sutherland delivered the majority opinion clearly. To all of the above questions, “No.”

There was an immediate ripple effect. Many Indian-Americans lost their citizenship. The Webb-Hanley Alien Land Law of 1913, which allowed only “aliens eligible to citizenship” to own land, meant that Indian-Americans who had bought land under their own name lost their property. By narrowly answering the question of who is an American, hundreds saw their rights denied or revoked, and the thousands who wanted to become an American were turned away before they could make their own journey.

Thind chose to remain in the United States. He went on to lecture and write books on topics ranging from metaphysics to spiritualism. In 1931, he married an American citizen, Vivien Davies. In 1936, he applied for citizenship in the state of New York and—by either luck or the activism of an anonymous Bureau of Naturalization agent—became a naturalized citizen.

It would do a nation well to remember the injustice suffered by Thind and countless others—an injustice in service of a skewed vision of what America should look like. Thind, like so many immigrants, sought out a new life, a better life, in America. It would do even better to remember that those who immigrate commit to a life of toil and sacrifice—and that America is the better for it.

© 2024