P.D. Soros Fellowship for New Americans

If you are an applicant and need to sign into the online application, you can find the link on the "Apply" page of our website: Apply Page.

If you are a fellow looking to login, please note that we are currently updating our backend system for managing Fellow data. In the meantime, to update your information for the Fellowship, please send updates to Nikka Landau at nlandau@pdsoros.org.

Kao Kalia Yang (2003 Fellow) Chronicles Her Father’s Life From Laos to Minnesota in "The Song Poet"

-

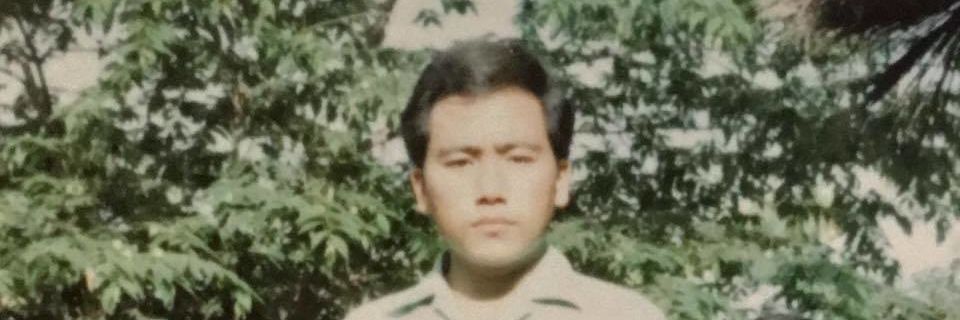

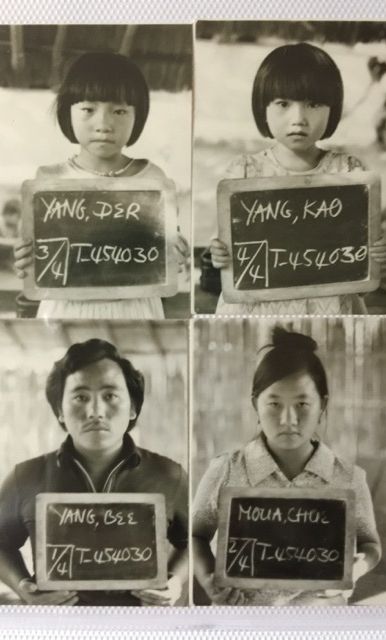

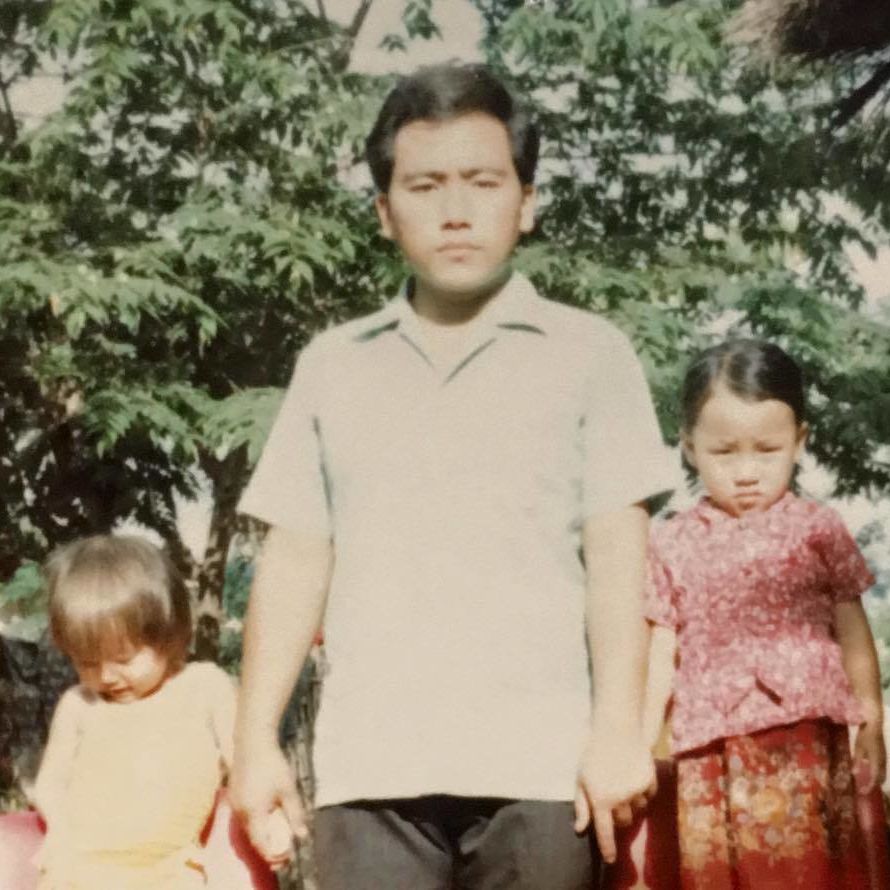

Images of Kao Kalia Yang's family taken in the refugee camp in Thailand where they lived for six years waiting for asylum in the United States.

Growing up in a refugee camp in Thailand, Kao Kalia Yang (2003 Fellow) relied on her father's stories to transport her to the world beyond the gates. Perched on her father's shoulders, Kalia would listen to his memories of growing up in Phou Khao, a village in the high mountains of northeastern Laos. He would tell her about life before the Vietnam War, before thousands upon thousands of Hmongs were recruited to do the United States' bidding in their fight against Communism.

He would tell her about life before he watched his village burn and took to life in the jungle. Living in a nearly microscopic camp along with some 40,000 fellow Hmongs, Kalia’s father’s stories helped everyone cope as they waited years for justice in the form of asylum.

"My father grew to become a young man in the jungles, no shoes on his feet, communal belongings on his back," Kalia explained. "It was in the jungles that he met my mother and married her. He was nineteen years old when he crossed the Mekong River with my mother, my sister, and my grandmother, into Thailand, where they waited in the refugee camp for a future to begin."

That future didn't come until July 27, 1987, six years later, when the family moved into a housing project in Minneapolis—a far cry from anything they, or any of the other thousands of Hmong families who were relocated there, were familiar with. Kalia's father began work in a factory, and a new life took shape.

"My father grew to become a young man in the jungles, no shoes on his feet, communal belongings on his back. It was in the jungles that he met my mother and married her. He was nineteen years old when he crossed the Mekong River with my mother, my sister, and my grandmother, into Thailand where they waited in the refugee camp for a future to begin."

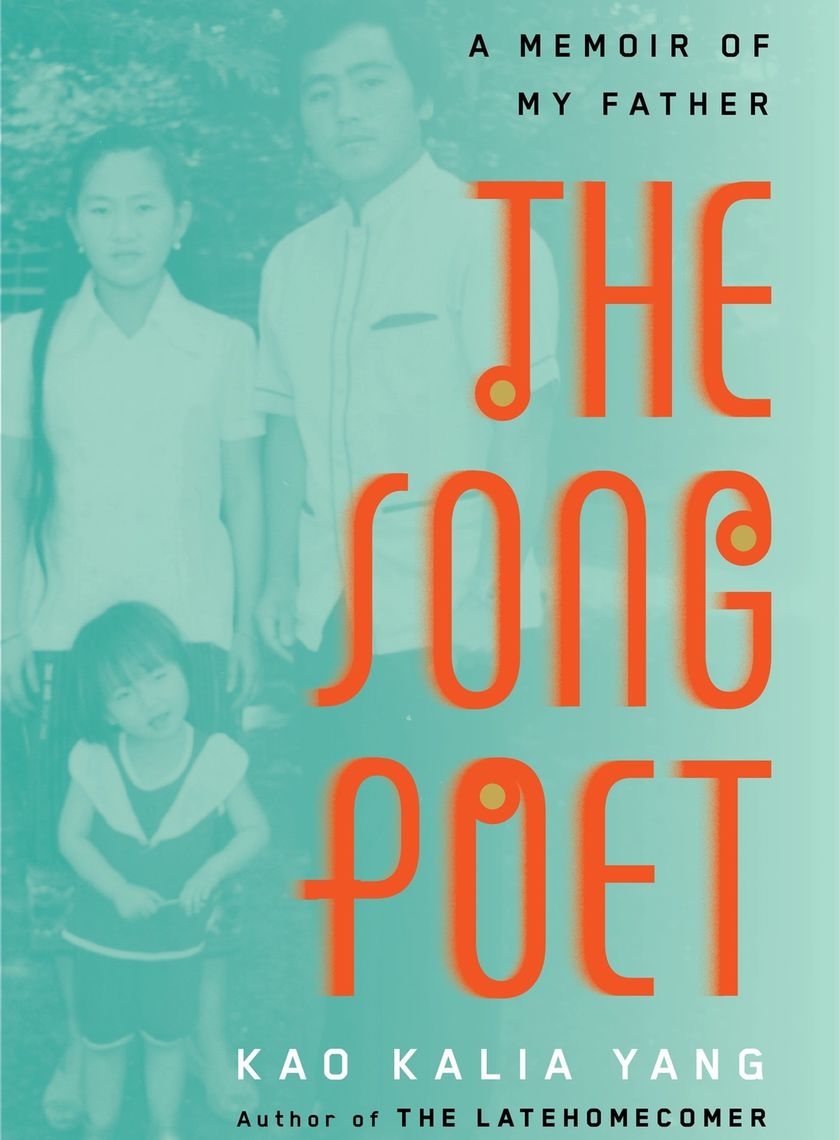

Now, decades later, Kalia is an author, activist, professor, and the mother of three children of her own. Kalia’s forthcoming book, The Song Poet, chronicles her father's life from Laos to Thailand to the United States.

While Kalia’s family embodies the American dream in many ways, Kalia is telling a much larger story. Like many Hmongs, her father lost a village, a community, and a country, and somehow that history is lost in the United States, their new home. To tell this complex story, Kalia is armed with the Hmong tradition of song poetry, kwv txhiaj, which she compares to a mix of jazz, blues, and rap. She employs Ralph Ellison’s description of the blues to help understand Hmong song poetry. Ellison described the blues as "an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one's aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near tragic, near-cosmic lyricism."

Kalia's father, as a song poet, was responsible for documenting the life and times of his community when he was growing up. His father died when he was young so he would visit with his neighbors, listen to their stories, and begin to weave them together. "For the Hmong, the song poet records and recounts the stories of his people, our history and tragedies, joys and losses; he keeps the past alive and the present in perspective," Kalia explained. This was an extraordinary skill as a father, in the refugee camp, and in the United States when it was even more important to keep the history alive.

"His expectations of himself and his children are high," Kalia said. "It is not the easiest to be loved for your best self, to be pushed for your furthest possibilities—all the time. It is hard to imagine who I am without my father's presence, his tireless guidance, his long reach."

Storytelling was only one of Kalia’s father’s talents though. Having grown up without a father, he has always tried to be the dad he imagined for himself. "His expectations of himself and his children are high," Kalia said. "It is not the easiest to be loved for your best self, to be pushed for your furthest possibilities—all the time. It is hard to imagine who I am without my father's presence, his tireless guidance, his long reach."

When asked what Kalia has learned from her father, Kalia has a hard time pinpointing just one thing. "What haven’t I learned?" she replies. "If I take into account all that I am and all that my father is, not in some distant future or faraway past, but right now in the middle of a cold Minnesota winter, hovering in our homes hoping for the happy that comes with spring...I've learned how to still my fluttering heart, to hold my hopes close and to cherish the joys of home in a world that can be so harsh."

A version of this article appears in the 2016-2017 edition of The New American.

A photo of Bee Yang with his daughters. Bee is the subject of Kao Kalia Yang's (2003 Fellow) book, "The Song Poet."

Kao Kalia Yang (2003 Fellow) is an author, activist and professor based in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

To learn more about Kao Kalia Yang and her book, The Song Poet, visit her website.

© 2024