P.D. Soros Fellowship for New Americans

If you are an applicant and need to sign into the online application, you can find the link on the "Apply" page of our website: Apply Page.

If you are a fellow looking to login, please note that we are currently updating our backend system for managing Fellow data. In the meantime, to update your information for the Fellowship, please send updates to Nikka Landau at nlandau@pdsoros.org.

The Most American Americans

It was a ghost town.

quiet streets. On the building walls, there were hundreds of photocopied handbills—the kind of “missing” posters one usually sees when a pet dog or cat has wandered off. But these had been placed there in mid-September 2001 by parents and spouses and children. They were desperate prayers that their loved ones be found and returned to their homes. And now, as more weeks passed and the fall turned colder, they stood as yellowed, weathered reproaches; symbols of hopelessness as opposed to a final hope. Because the sons and wives and fathers and mothers had not wandered off. They were not just missing. And they would not be returning home. The gray powder that covered the ground we walked on was not just pulverized concrete. It was ash.

His parents were both children of concentration camp survivors and grew up in Communist Czechoslovakia.

Andrei’s desire to find ways to serve took him from a Cub Scout to eight years as an officer in the Navy Reserve.

That Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowships Fall Conference fifteen years ago was a somber one. Certainly, we were in a city and country still fundamentally shaken. And the experience of walking amid the ruins was searing and unforgettable. But there was something more personal as well. The target had not just been the Twin Towers; it was an attack on us—or rather on the idea that we had been brought

together to represent.

The idea is at the heart of the Fellowships, and it represents the best of our national experience. It holds that there is no one “truth,” that we come from all parts of the globe bringing different views and traditions. And at the same time, that we are not defined by the history our families left behind;

that there are universal beliefs that bind us together. This idea that pluralism and unity go hand in hand—e pluribus unum—means we can be both “New” and “American” and that putting those words together is being consistent and not contradictory.

This notion clashed with the 9/11 attackers’ vision for homogeneity and sectarianism just as it does with those contemporary native voices who would have us believe a person’s actions are essentially defined by their religion or their ethnicity. But though it has always been contested, this idea is also elemental. “What, then, is the American, this new man?” asked French immigrant farmer J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur in 1782. He answered his own question: “The American is a new man, who acts upon new principles; he must therefore entertain new ideas, and form new opinions.”

If that inventiveness and innovation are essential to Americans, then it is immigrants and children of immigrants who are the most paradigmatic Americans of all. They founded Apple, Amazon, eBay,

IBM, GE, and Google. They invented basketball, and hot dogs, and the telephone. They gave us Mickey Mouse and McDonald’s, the Bank of America and “God Bless America.”

As much appropriate discussion as there is of the rights of immigrants, there is far too little

conversation about how New Americans live up to their unique responsibilities to bring their striving

spirit to the nation. Numerous studies show they study more and work harder. The reasons go deeper

than family pressure or economic need. So many New Americans feel a duty to contribute, to make a mark, to muscle their way into the center of the story.

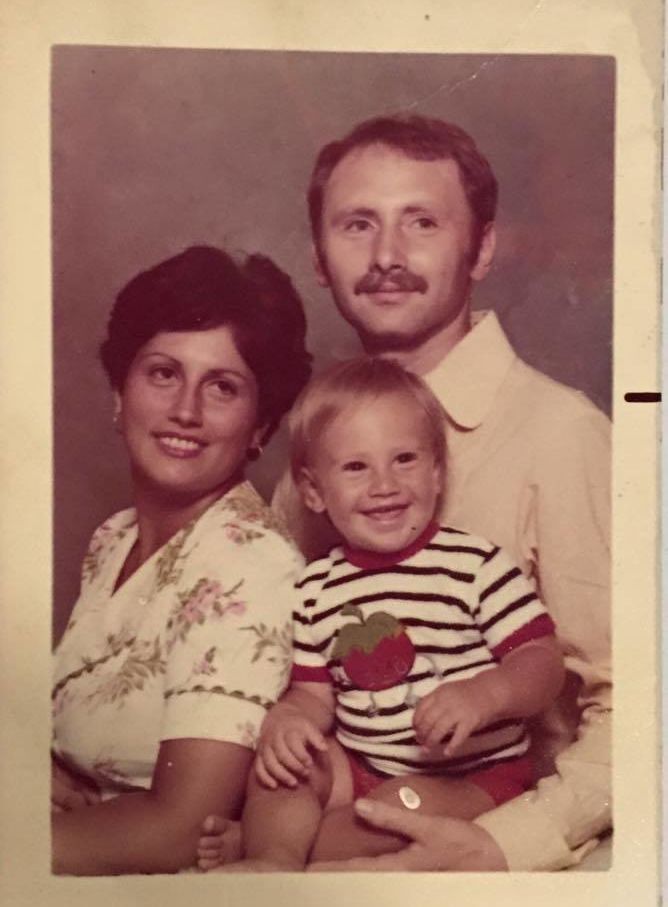

My parents grew up in Communist Czechoslovakia as the children of concentration camp survivors.

America gave them a home just a couple of years before I was born. I grew up in an apartment building in Los Angeles, where our neighbors and best friends came from Guatemala and Jamaica and Japan. From the time I was young, I felt a profound sense of gratitude and an immense desire to weave my own life into the fabric of America. From public service to military service to writing works of American history to my present work with Aspiration, I’ve searched for ways to make a contribution and a connection. My story is not exceptional. In fact, what makes it noteworthy is that it is so commonplace.

To spend time with new Paul & Daisy Soros Fellows or to serve on interview panels or to merely leaf

through the bios of incoming classes is to be at once supremely humbled and extremely reassured

about the future. And to get to observe now nearly two decades of Fellows advance through their

lives is to see the true engine of national greatness at work. Physicists and physicians. Playwrights

and poets and pianists. Ambassadors and professors and producers and public interest lawyers. CEOs and scientists and surgeons and even a surgeon general. The achievements are awesome. They should

be rightfully celebrated. They are just a preview of what past and future Fellows are yet to achieve.

But these accomplishments, in and of themselves, do not define the immigrant experience. Rather, what’s most indispensable is the striving and searching that power the accomplishment.

That struggle is the universal experience of immigrants in America. Paul & Daisy Soros Fellows

are chosen for the honor at a moment when they are accumulating multiple degrees from America’s

esteemed institutions of higher education, but rewind the clock on their and their families’ lives

for a generation, or even often just a few years, and you see that same determination going into

learning an unfamiliar new language or working a day job while still exhausted from having pulled

the night shift.

-

Andrei (right) and Nusrat Choudhury (2004) discussed building a public voice at the 2015 Fall Conference. Photo: Christopher Smith.

That grit and resolve is the through-line of the New American experience. It is what connects the Fellow celebrating in her cap and gown to those who sweep up long after the graduation festivities are over; it unites together those who landed at Ellis Island and those who land at LAX; it binds together those whose homes we visit at the Tenement Museum on Orchard Street to those who live today in crowded apartments spilling over with foreign tongues just a few blocks away; it is the link between those who cut a clearing in the wilderness after landing on the Mayflower and those arriving in 2016 after a harrowing journey across the Mediterranean; it is the story of a refugee from a war-torn land who came to America with $17 in his pocket and turned it into a fortune that he, together with his wife, Daisy, would eventually use to give other young immigrants and children of immigrants their own chance at opportunity.

That relentless effort, that spirit of invention and reinvention, is what is definitional in the American

character. And it is found most of all in the newest Americans. Calling someone a New American is really just saying the same thing twice. It is America’s immigrants who are in so many ways the most

American Americans of all. And it is they who today, as they have throughout our past, are making

America great again...and again, and again. ∎

This article originally appeared in the 2016-2017 edition of The New American.

Andrei Cherny, the son of Czechoslovakian immigrants, is a former White House speechwriter, former Arizona assistant attorney general, and the founder and CEO of Aspiration, a new kind of financial firm: one for the middle class.

© 2024