P.D. Soros Fellowship for New Americans

If you are an applicant and need to sign into the online application, you can find the link on the "Apply" page of our website: Apply Page.

If you are a fellow looking to login, please note that we are currently updating our backend system for managing Fellow data. In the meantime, to update your information for the Fellowship, please send updates to Nikka Landau at nlandau@pdsoros.org.

Q&A: Emily Martin's New Book of Poetry

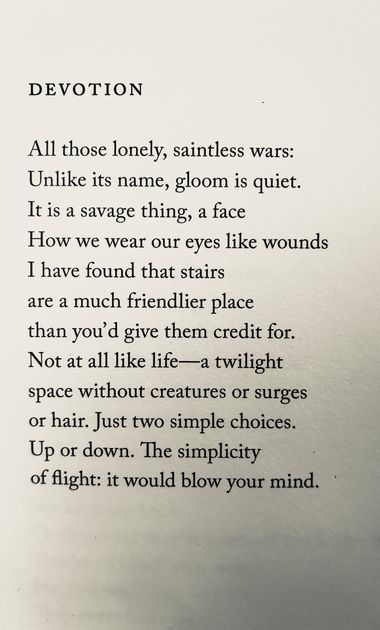

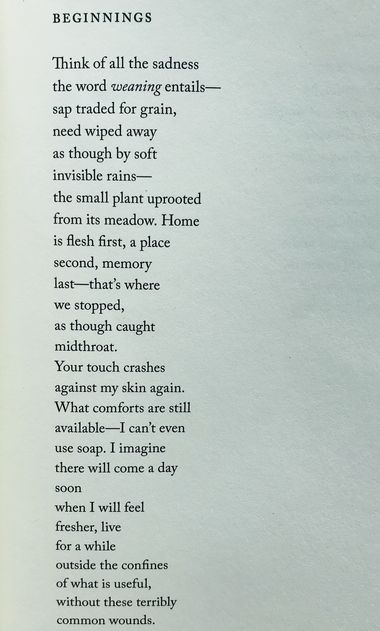

Poet and 2010 Paul & Daisy Soros Fellow Emily Charlotte Martin’s debut book of poetry Objects of Hunger was recently published by Southern Illinois University Press and is the winner of the Crab Orchard Series in Poetry.

Emily, who publishes under her maiden name E.C. Belli, is an Anglo-Swiss poet and translator. She was born in Switzerland and attended Columbia University for both her undergraduate and graduate studies.

We asked Emily about her new book, her writing process, and her inspiration.

When did you begin working on Objects of Hunger?

I have a terrible memory and an even worse time keeping papers and documents organized, but many of the poems were written in 2014. Since many of these poems were process poems that included word mining, collage, etc., I revisited them over the years, trying to drag them further and further from their inspiration source, seeing how far they could land, if they’d grow wings. I cut out some pieces altogether when the echoes of the old sufferers felt too present, even after many changes. I had to develop a feeling for when I’d reached the right distance from the primary materials, whether it was a new work that made sense on its own.

World War l and Virginia Woolf are both rooted in the work. What is the thread or theme that ties the poetry together for you?

It’s about the lexicon, I think. There was a strange and unexpected linguistic overlap in what I was reading and the language of birth (which doesn’t equate these vastly disparate and unequal experiences, of course—let’s not be reductive—but perhaps that all made it stranger yet and thus interesting to explore). I wanted to see how far that language could go in a domestic context, handling pedestrian themes of love, need, want, desire, etc. I was shocked; it went far.

What is your process for writing a book of poetry? How did you know when you had finished?

I didn’t have a planned process, although I find more and more that I enjoy creating things in a short span of time (5 days, 15 days, 30 days) because the results are of one impulse in terms of emotional homogeneity. Process was revealed in hindsight. With other living and breathing priorities, the difficulty at the time was finding time alone to type; I wrote a lot by hand, walking around, going places, and then typed up the work later. I think that may affect the pacing. I could have continued to add or remove poems. It could have been a different book. What makes it feel complete is that, emotionally, it said all I had to say for a given period of time. That’s actually one of the most discomforting things about a book of poems. Things end up frozen in time, and this is quite inorganic, this crystallization. Feelings move forward, ideas develop, aesthetics change, but the poems stay. I kept thinking, I hope I get done before I start unbelieving everything written. Poems are like these friends who never forget anything you tell them. The speaker, who utters an emotional truth the writer must have known, will keep uttering the truth even after the writer has moved on to other truths. Therein lies the difference between writer of a poem and speaker: the speaker is the mouthpiece for an emotion felt by the writer at one precise instant in time (in conditions the poems don't always relate back, or relate back partially, or transform). Writers are many-speakered in that way.

When do you choose to write in English versus French?

I’d always thought my first book, if chance was given, would be in French. I love French. It’s my heart language. I write a lot in French. I spend as much of my day immersed in it as possible, translating, reading, etc.. And I am a translator at heart. I’m much more spontaneous in French, much funnier. English is my mother tongue (I learned it from my mother, while French was my father). Mothers are very serious business. I work in English, but I feel in French. I ended up publishing more in English because the process is more streamlined, there are more opportunities, and also perhaps because I feel like a visitor sometimes in this language (as it is less aligned to my inner being, although I’ve always spoken both), and so the opportunity for play is greater. You don’t play with your food, and French is my food. English is the furniture inside my house, the bed to sleep on. I control what it does to me more. I can move the furniture around. But I can’t let an apple roll onto the floor just to see what happens. It would be disrespectful. Actually, a strange reverence kept me, for a long time, from doing to the French language what I needed to do to in order to make any interesting work. I have a few interesting pieces only now.

How does this book connect to your New American story?

The community aspect of the fellowship has been so life-giving I barely dare to utter it. It makes my heart so complete to have these individuals in my life, and I think it gave me the courage to keep believing in myself in moments when I wasn’t very inclined to. The friends, confidants, supporters, and thinkers I have been lucky to connect with through the fellowship make up the largest portion of my social life and fill me with endless fascination. I just don’t know what I would have done without it from a social standpoint. It also motivates me to get up in the morning…I get to have the luxury of exchanges with such brilliant minds. Some people have sports cars. I have a cohort with the most tender hearts and the most astounding minds, which proves that, really, the world can be a beautiful place.

You have three kids. How have they changed your writing?

I never talk about them. They are my everything. Privacy is a privilege that is increasingly slipping away from individuals of their generation, so I’ve chosen to not include them at all in what I write. Love, on the other hand, is fair game.© 2024