P.D. Soros Fellowship for New Americans

If you are an applicant and need to sign into the online application, you can find the link on the "Apply" page of our website: Apply Page.

If you are a fellow looking to login, please note that we are currently updating our backend system for managing Fellow data. In the meantime, to update your information for the Fellowship, please send updates to Nikka Landau at nlandau@pdsoros.org.

Share

Anthony Veasna So In His Own Words

12.16.20

2018 Paul & Daisy Soros Fellow Anthony Veasna So took over The Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowships for New Americans Instagram account to share his personal story in December of 2018. Anthony passed away in December of 2020. We have published Anthony's Instagram posts here.

Two of the posts on Instagram included videos; we've only included screenshots of those videos below.

December 23, 2018

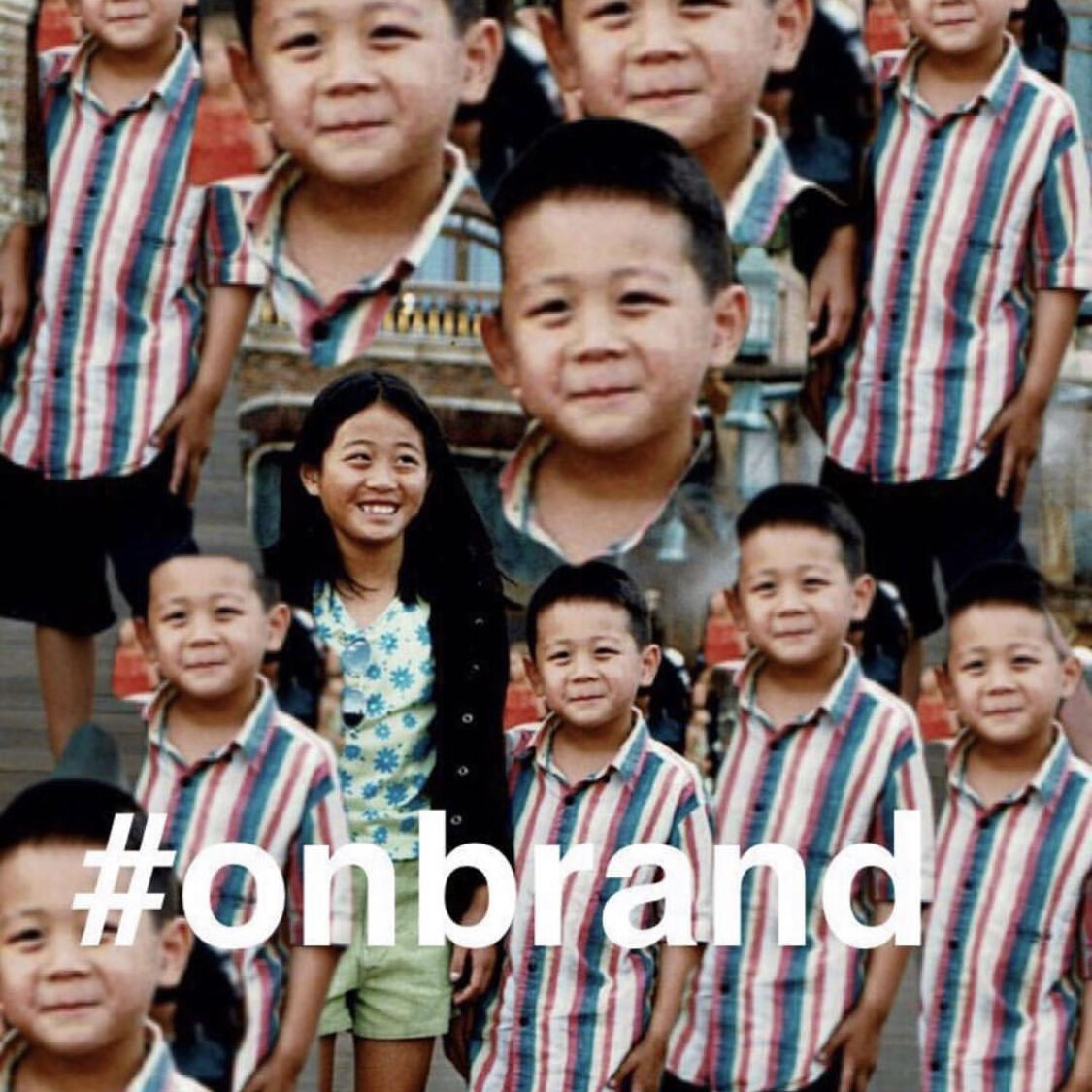

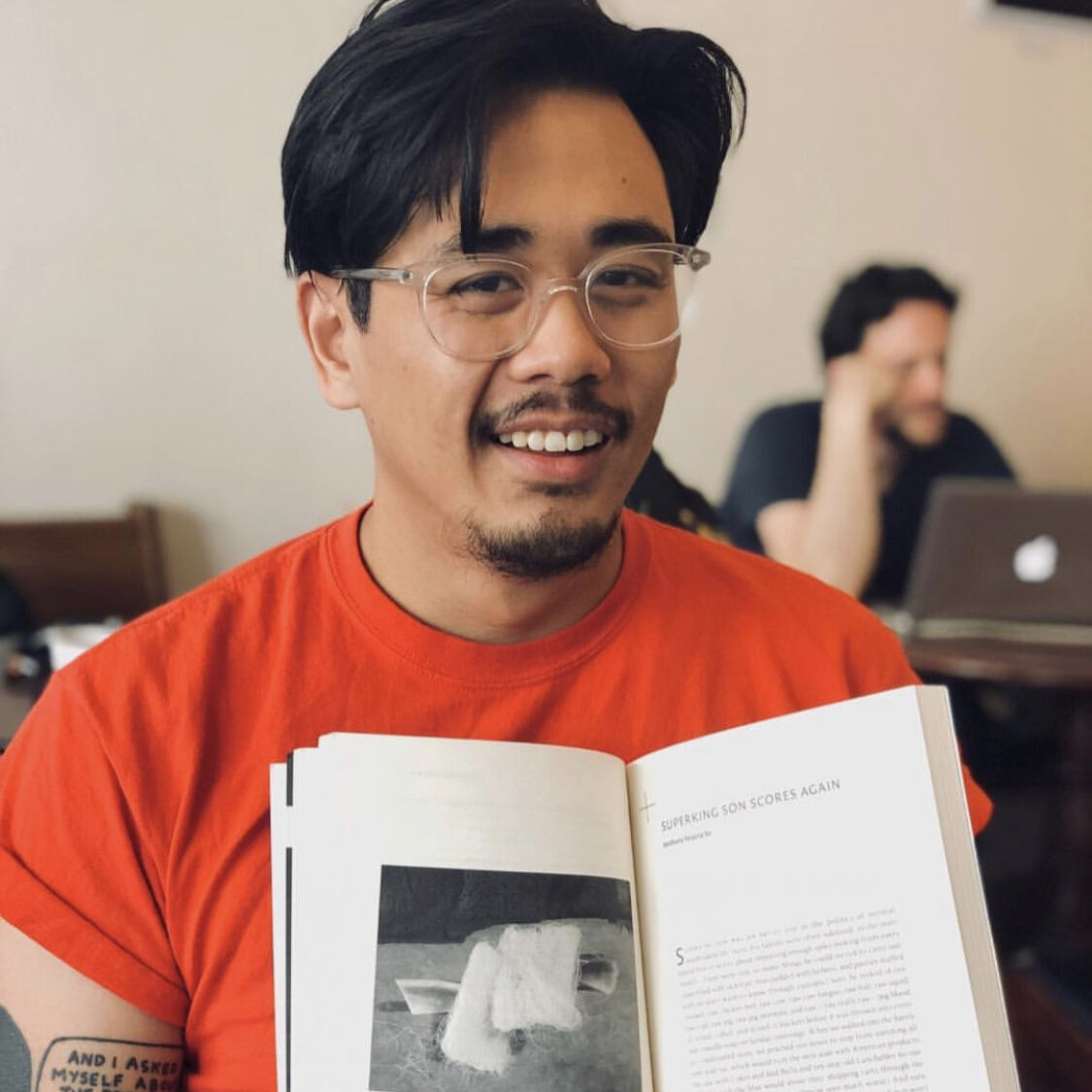

Hi, my name is Anthony Veasna So. I’m going to be doing the Instagram stuff this week. I’m currently doing my Masters in Fine Arts in Fiction at Syracuse University, where I am working on a story collection and novel about the lives of post-genocide Cambodian-Americans. I grew up in Stockton, CA, where my parents and a bunch of other Cambos immigrated as refugees of the Khmer Rouge Genocide. As a kid, I heard traumatic stories of my family’s experience surviving the war/Pol Pot’s regime that somehow always landed on a joke, on some irreverent yet hopeful gesture to claim ownership over our brutal history. More on that later, but because of these family stories, I knew I wanted to be a writer/artist of some sort, which meant that as a kid, like all writers, I was simultaneously narcissistic (note first pic) and deeply introspective/aka angsty (note second pic). Now I’m living the dream of being paid to write, which mostly just means sitting in cafes and staring at my laptop and then forcing my boyfriend to take pics of me when I get writer’s block (note third pic). Anyway, looking forward to doing what I do best on the PD Soros Instagram—going on and on about myself and saying it’s “literary.”

December 24, 2018

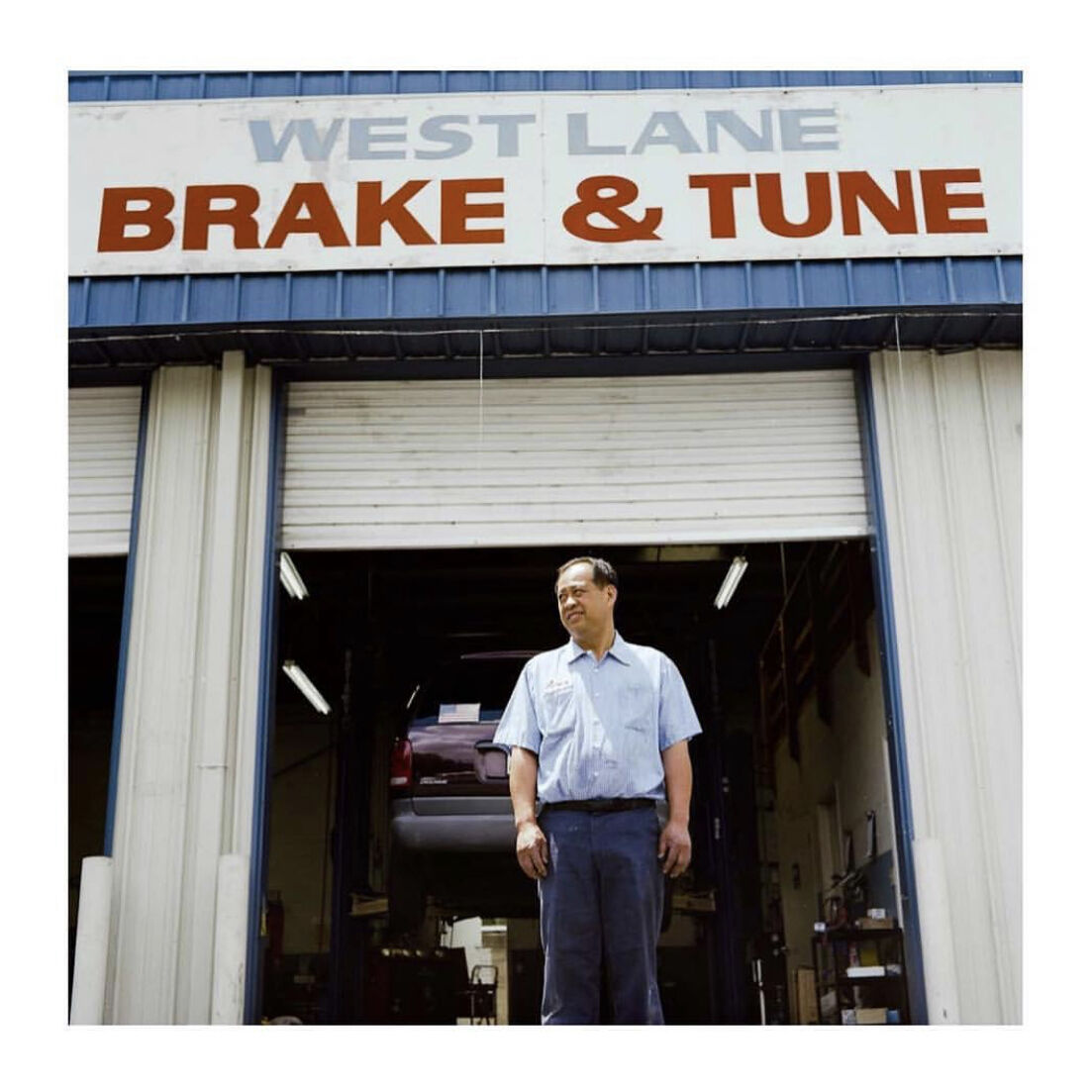

One of my dad’s favorite jokes is that because he survived the genocide, he’s now prepared to be a contestant on and win the reality tv show, “Survivor.” A son of a farmer and teacher—my grandpa—my dad was only 12 when Pol Pot took over and sent his whole family to slave away in the rice fields and undergo brutal torture. Years later, my dad led other families through the mine-encrusted forest to get to the Thai border and escape, as he was the only person who knew his way through the landmines. In 1980, he came to the U.S. as a refugee and started studying for his Associate’s Degree at the community college, even though he didn’t speak English, had only a sixth grade education, and quite literally had nothing to his name. Supporting himself the whole way, my dad earned his certification to be a car mechanic, and after years of working as a mechanic, he opened his own car repair shop.

I spent most of my childhood working at my dad’s shop, using old newspapers to clean the windows to save money. My dad would crack jokes whenever I complained about working, telling me that “These chores are nothing compared to working in the rice fields.” When I got into Stanford, my dad was proud beyond belief (note the last picture of me and my dad at the Rose Bowl in 2013, when Stanford won. I hate football, but my dad makes me go to Stanford games with him). I am a first-generation college student, and I never forget how hard my parents worked to support me. — Anthony Veasna So, 2018 Fellow, MFA candidate in Fiction

December 24, 2018

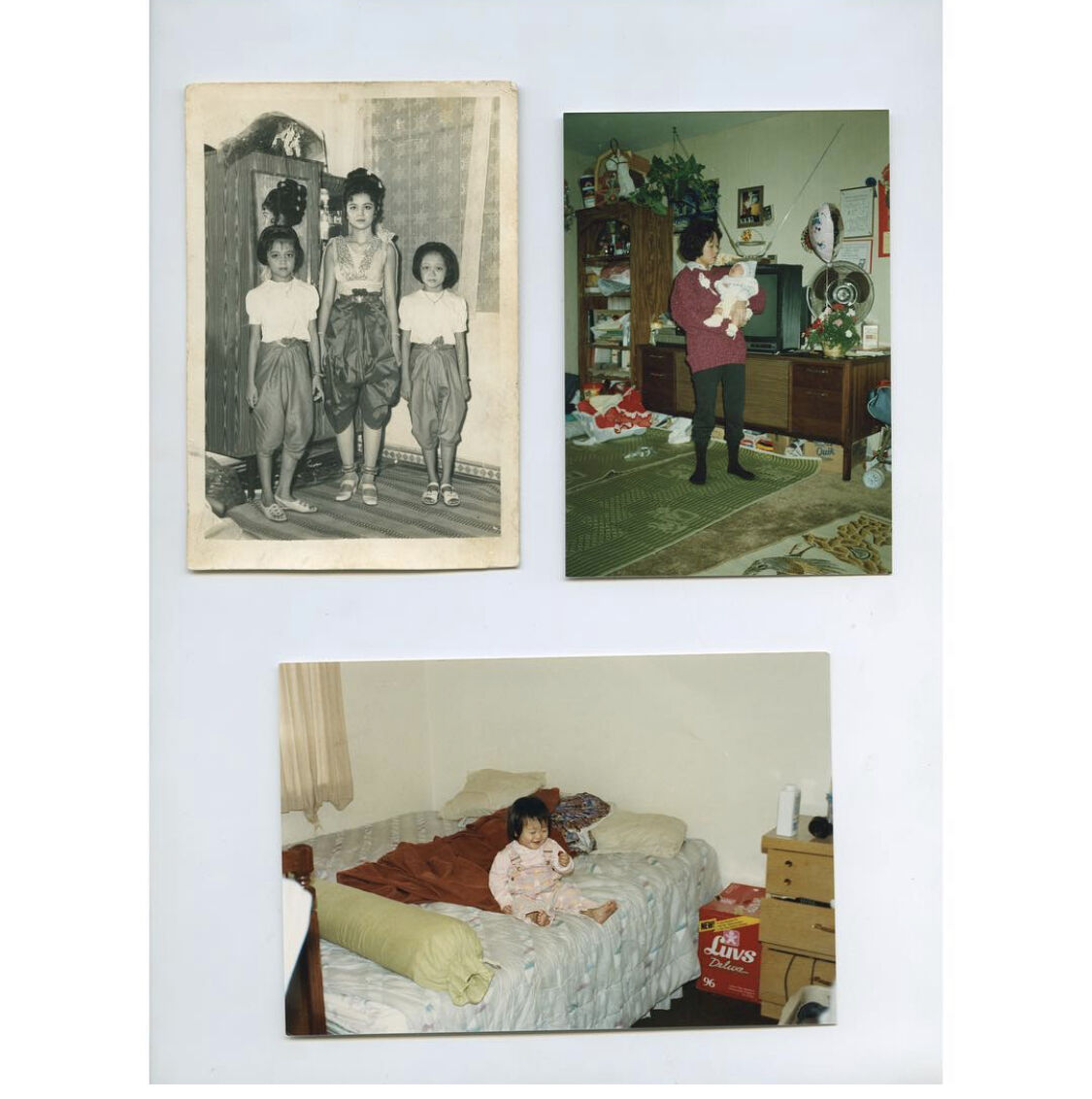

My mom is the smartest person I know. Like my dad, she came to the U.S. as an 18 year old refugee of the Khmer Rouge Genocide, with a sixth grade education, and worked her ass off to get her associates degree from the community college. She wanted to go on and get a BA, but she couldn’t afford it. She didn’t know any English when first immigrating, but she mastered the language so well that all throughout my high school, she corrected my grammar on my papers. In 1989, she was working as a bilingual aide at Cleveland Elementary School, the year a mass shooter shot up the school’s playground with an AK-47 because he thought the neighborhood was being taken over by brown refugees. Five Southeast Asian kids died, and many more were injured. I remember asking my mom about what that day was like for her, and she joked, “what’s new? I always find myself in regimes.” My favorite story of hers involves my dad. He was leading her, her family, and others through the forests to get to Thailand. My mom was a teenager and painfully shy, having spent her adolescence in concentration camps. She was painfully thirsty, and she hated my dad, because the entire time, my dad had two water bottles—one for drinking, and the other for splashing all over his face. My mom looked at my future dad, and thought to herself, “I’m dying of thirst, and here is this arrogant boy, and he’s giving himself a shower in the middle of the forest! WHY? We’re in the forest!” — Anthony Veasna So, 2018 Fellow, MFA Candidate in Fiction

December 25, 2018

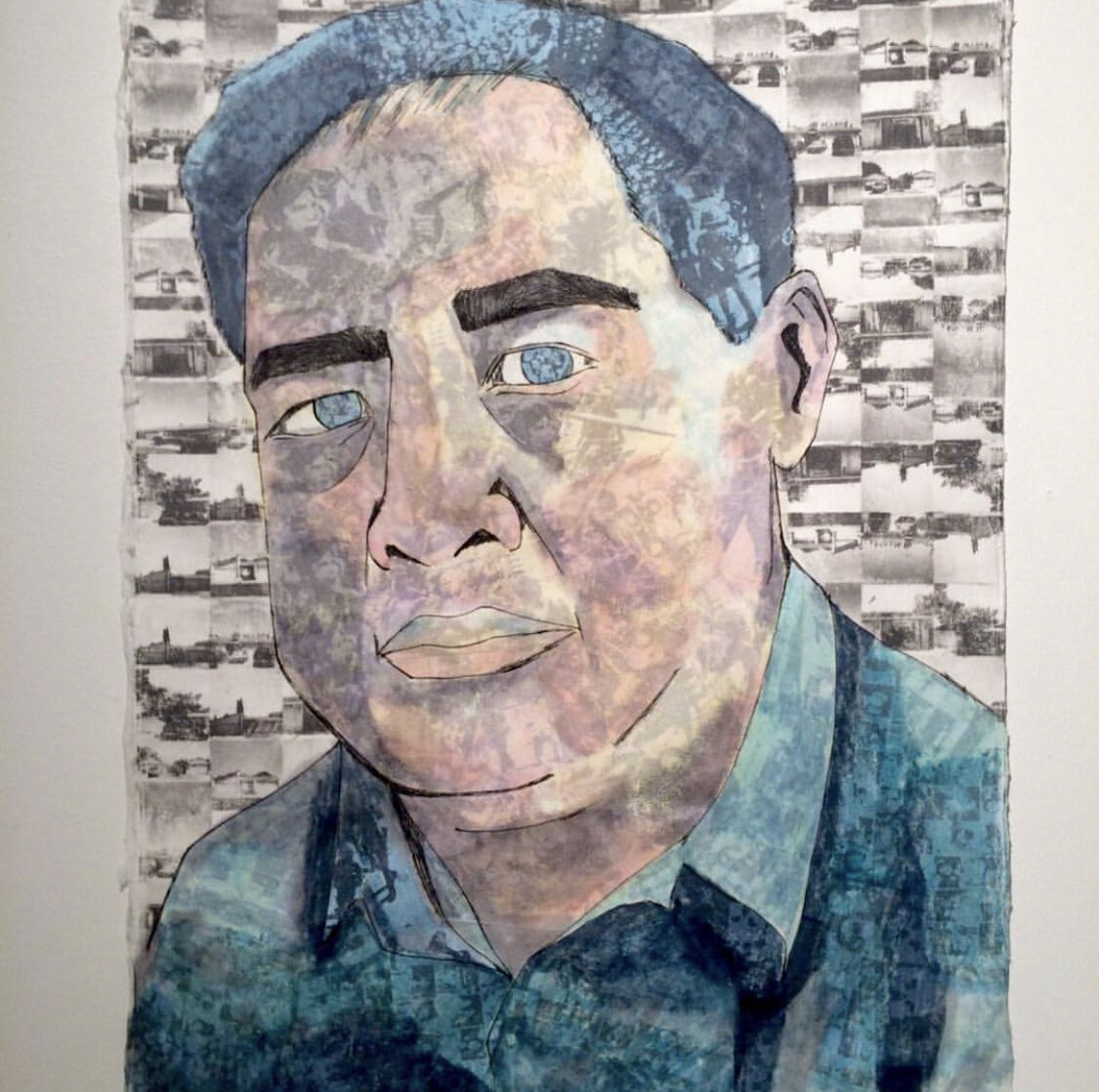

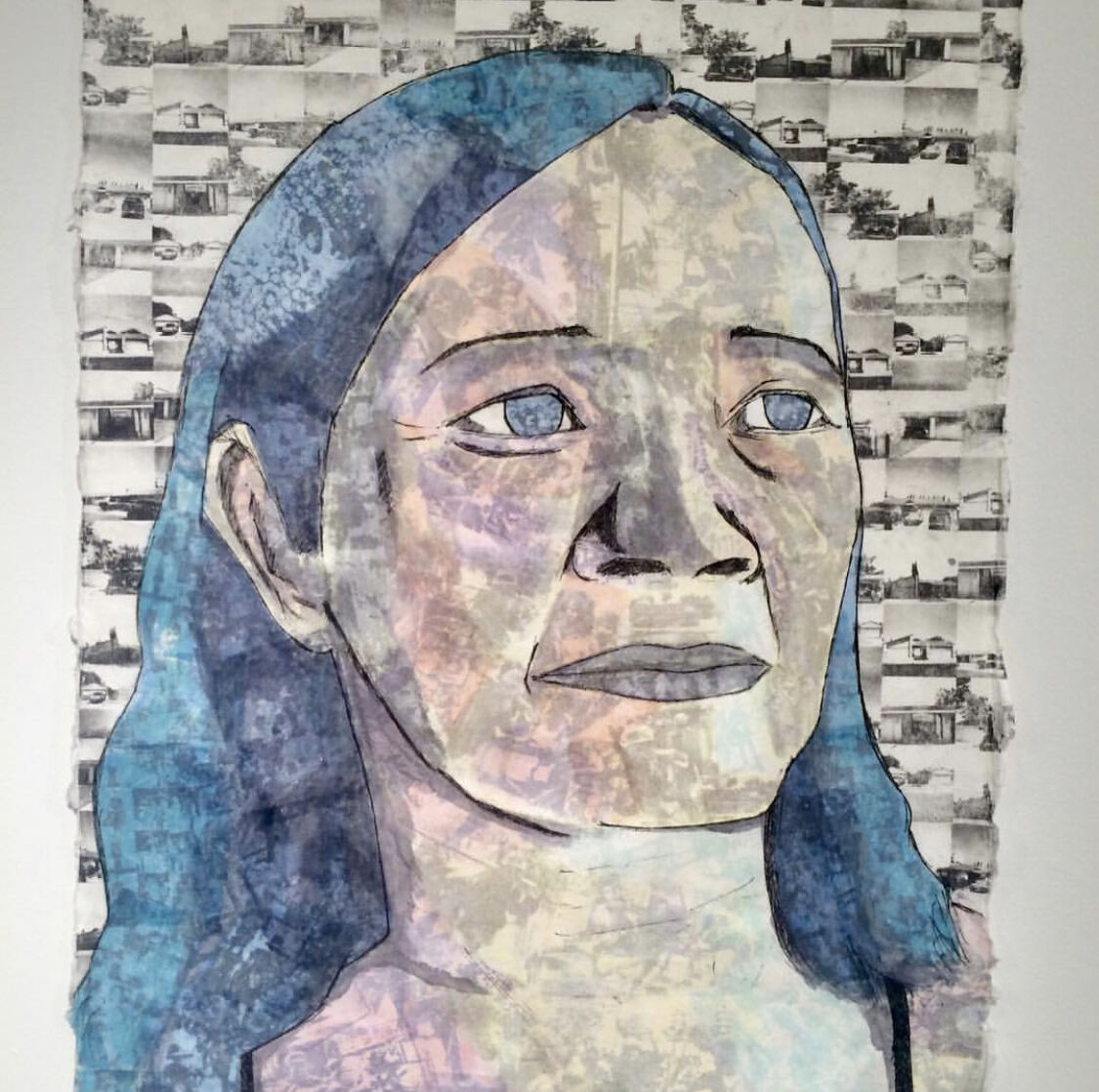

Although my work now mostly revolves around fiction and literature, I started off my undergraduate degree as a studio art major, eventually double majoring in both Art and English Literature at Stanford. Visual art heavily influences my current work and the way I see the world. I often get questions as to why I chose to pursue the arts and creative writing, versus something more practical, and the question really astonishes me. In any oppressive regime, dictators and tyrannical rulers make a point to attack and destroy the arts. They uphold censorship laws and attempt to dictate the ways in which we express ourselves. During the Khmer Rouge Regime, Pol Pot wanted to restart the country at year zero, so he incinerated entire libraries, and killed the teachers, artists, writers, and intellectuals first. Writers and artists have the power to cement history into our cultural fabric. They manifest the process of remembering in their work, while also helping the oppressed imagine new reparative futures. And this power poses a threat to oppressive regimes. I pursued the arts because I want to never forget my own history, and I want to do my part in making sure this history is never lost for others. I want to pave new futures for my people. Most of my own visual art, like my fiction, draws upon my parents’ refugee experience. I made these rice paper portraits, based off of medium format film photos I took of my parents, through a print transfer process that involves using wintergreen oil to etch an image onto another surface. The images I collaged to create my parents‘ faces consist of archival imagery from the Khmer Genocide, which I painted in different bright colors, while the backdrop is a cascade pattern of the rental properties my parents invested their life savings into and renovated themselves after 30 years of working and saving in the U.S. — Anthony Veasna So, 2018 Fellow, MFA Candidate in Fiction

December 25, 2018

Here’s my obligatory Xmas post. My family isn’t particularly attached to Xmas in a cultural or religious way—we’re mostly lite-Buddhist. But we do take any opportunity to eat a ton of food, all dressed in the same t shirt nonetheless. My aunt and uncle host Xmas every year and they make crab, lobster, clams, duck, fried fish rolls, quail, fried rice, etc... (note the third vid for close ups of the food). As you can tell, I grew up in a giant family. Because our parents were always working overtime or second jobs, my grandma (front left) took care of me and my 10 other cousins after school and over the summer. I can’t even imagine how hard that must of been, since my cousins and I were a rowdy bunch. Feeding us alone was stressful as heck. Whenever my grandma found out we liked some particular food, that’s all we ate for weeks. One summer, the only thing we ever ate for lunch was canned Stagg chili. My cousins are like my siblings. We all went to the same high school, and without the guidance of my older cousins, I wouldn’t have excelled in school or even applied to college. Happy holidays! — Anthony Veasna So, 2018 Fellow, MFA Candidate in Fiction

Anthony added the following in the comments: Also note that deal or no deal is playing on the tv in the background—that and family feud are my grandmas favorite shows lol.

December 27, 2018

This past year I achieved something major in terms of my writing career. I scored my first print publication in a big literary journal. The first story I wrote and finished in my grad program at Syracuse, “Superking Son Scores Again” probably is the most “Stockton” (my hometown, which is home to one of the biggest Cambodian-American communities in the U.S.) story I’ve ever written. Also, it’s about some of the defining things of my childhood—badminton, Cambo grocery stores, inherited trauma, pursuing your passions when your whole world is at siege. It’s the 8000 word short story about badminton the world has been begging for up until now! Anyway, this story publication was huge for me. It boosted my confidence in my own work, and connected me to a literary community I really love and respect and learn from. n+1 has been great to me, and through their editorial team, I’ve also gained two additional publications in their journal (another story about chain-smoking Buddhist monks and a personal essay about watching “Crazy Rich Asians”). This publication also helped me attract the attention of and sign with my current literary agent—a great agent and editor who represents many poc and immigrant writers I love. (If you’re unfamiliar with the publishing world, you basically need an agent to sell your book to a major publishing house). This is just to share some major breakthroughs for me, other than getting the Soros of course! — Anthony Veasna So, 2018 Fellow, MFA Candidate in Fiction

December 28, 2018

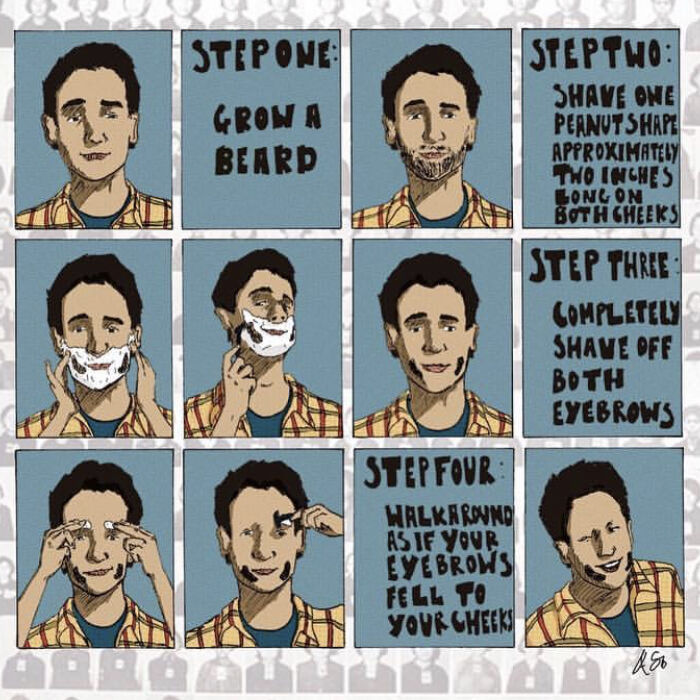

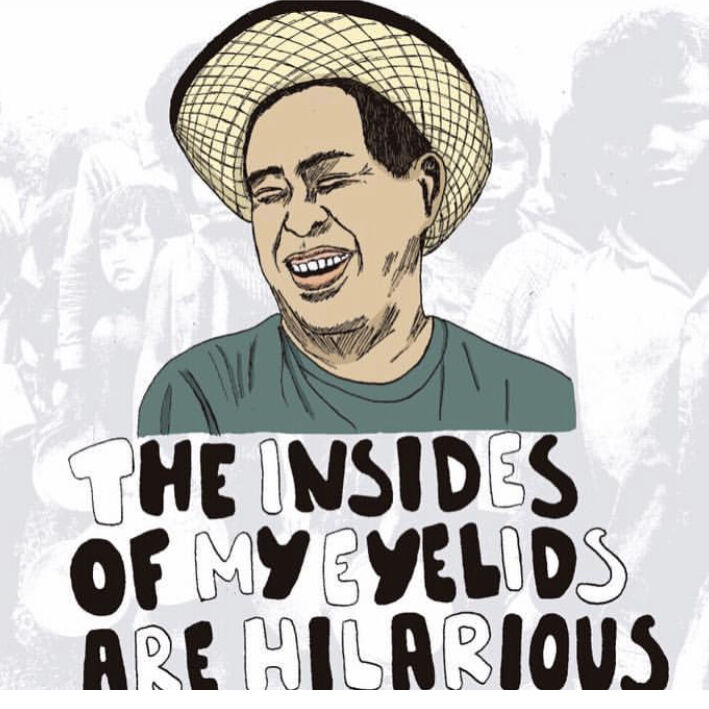

Throughout my time at Stanford, I did a lot of standup comedy, even spending a couple of summers in NYC and LA doing open mics every night, and I still use a lot of my training in comedy in my short stories and in my comics. I think humor is a particularly important tool in immigrant literature and stories, or anyone who is marginalized. For one, my own parents are hilarious. They are constantly making jokes about their traumatic experience. But also, there’a theory of humor I love, first started by Immanuel Kant, I believe, that states that humor arises from incongruence. Something violates our mental patterns and expectations, and our expectations are subverted—the joke’s punchline subverts the set up. At the very core of a marginalized person’s experience is an incongruence, a misunderstanding. The culture of the marginalized and the culture of the dominant power don’t match. Humor is a tool for marginalized people to shed light on this incongruence, to focus people’s attention onto it, so that they can realize that political action needs to be taken in order to reconcile said incongruence. — Anthony Veasna So, 2018 Fellow, MFA Candidate in Fiction

December 29, 2018

For my last post of the week, I wanted to post these two selfies. One, I think that it’s just sort of hilarious for me to post selfies on the pdsoros Instagram. But also, I haven’t spoken about being queer yet and what is more queer male than taking a mirror selfie. Plus, these two photos are pretty meaningful. This first photo was taken the night after my soros interview. I remember being so enthralled by all the interesting awesome soros applicants I was meeting and wanting very much to become a part of the community. The second photo features me in a Khmer krama scarf, a traditional Cambodian piece of attire. Over the past couple of years, I’ve worked to love myself as not just a queer man and not just a Cambodian American, but as a queer Cambo. Anyway, it’s been great gang. Follow me @fakemaddoxjolie if you want to connect. — Anthony Veasna So, 2018 Fellow, MFA Candidate in Fiction

© 2024