P.D. Soros Fellowship for New Americans

If you are an applicant and need to sign into the online application, you can find the link on the "Apply" page of our website: Apply Page.

If you are a fellow looking to login, please note that we are currently updating our backend system for managing Fellow data. In the meantime, to update your information for the Fellowship, please send updates to Nikka Landau at nlandau@pdsoros.org.

Five Questions for Henry Wei Leung (2012 Fellow)

Not every Fulbright Scholar finds themselves camping on the side of a road, but for Henry Wei Leung, who pursued a Fulbright in Hong Kong in 2014, camping was one of the most meaningful experiences of his year. That's because he did it as part of the historical Umbrella Movement protests.

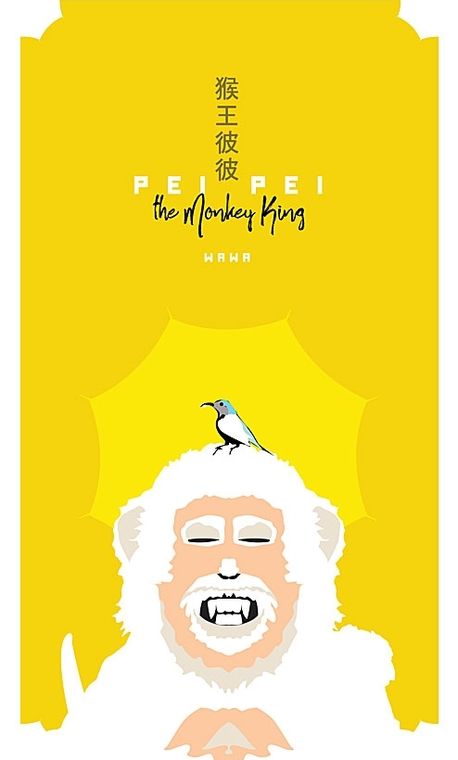

But Henry had gone to Hong Kong with a different purpose: to discover an unheard-of local literature. This fall, Pei Pei the Monkey King, a book of poems by a Hong Kong poet, was published bilingually with Henry's translations and a critical introduction on the linguistic and political situation in Hong Kong. As Henry put it, "It wasn't my Fulbright project but it is in some ways the culmination of my year there [Hong Kong] on a Fulbright grant during the protests for democracy."

Henry is pursuing his PhD in English Literature at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa, where he also teaches courses connecting political activism with literary engagement. He is currently the Managing Editor of the Hawai'i Review.

Here's our interview with Henry on his newest book:

Your new book of poems is a bilingual compilation of Wawa’s poems. Can you tell us about Wawa who is a Hong Kong poet?

My original plan was to go to Hong Kong to seek out an aesthetic consciousness unique to that city, especially in the unique collision (though not necessarily the admixture) of Englishes and Chineses. Basically, I wanted to find a poetic consciousness that was not merely British (colonial) nor American (aspirant) nor "Chinese" (mainland China), but was Hong Kong on its own terms. This turned out to be magnificently difficult; even the Chinese-language writers who are hailed locally had to first "make it" by being published abroad, usually in Taiwan. Same with Wawa; this book, which is an eminently Hong Kong book, had to be published by an American press. I would say there still isn't a recognized Hong Kong literary sensibility, though it does exist in the shadows of a largely hostile, and still fairly colonial, publishing enterprise. Wawa is one such example of a real poet--an anachronism in her city in its time--who is not writing about Hong Kong but is writing Hong Kong. She comes from a background in Philosophy, and has made the compelling claim that philosophers have become academics today. But poets, she says, poets are still doing the work of philosophy, creating worlds and systems. (We might both note, though, that this may be true of only very few poets, especially given the recent institutionalization of poetry as an artisan's craft.)

You did your Fulbright in Hong Kong. Is that the origin of this project?

I was on a Fulbright grant intending to research the literature from a linguistic vantage point. My project was yanked down a sharp detour by the Umbrella Revolution protests, which broke out shortly after arrived, and which ended up being the primary focus of my time there. These were protests ostensibly for universal suffrage, but their larger implications (which have already played out in many political developments since then) were against the infringement of mainland Communist China, not as a "mother country" but as a second colonial force circumscribing the legal provisions for Hong Kong's autonomy, identity, and, ultimately, dignity. Wawa was among the first to be teargassed at the start of those protests on September 28, 2014, and by the time I met her, my research had already become about this precise intersection between the political and the poetic there.

Which is your favorite poem?

The most untranslatable ones are always the translator's favorites, I suppose. "The Great Rock Has Returned," which is excerpted on the Tinfish Press site, is among the more Cantonese of the poems, and required some play or experimentation to at least acknowledge (though it can't account for) what is lost in the move between languages. I address this more thoroughly in the critical introduction. In Hong Kong, "Chinese" is not Chinese. There are all the political layers implied here, of course, but even on the linguistic level, we're talking about Cantonese, Mandarin, Traditional, Simplified, "written Chinese," and all the gaps in between. So to write in Chinese in Hong Kong is to already have lost something in translation; how much more so to then translate such a text into English. The protests, and all the complexity of international English-language voyeurism fixed upon them, also encapsulated much of this for me.

What is the main focus of your PhD studies in Hawaii?

Poetry; activism; postcolonialism; indigenous resurgence; the decolonization of language.

What’s your next project?

I'm getting restless in academia and its surplus labors. I have a novel in the works (a still unfinished mammoth of a project from my time as a PD Soros Fellow!), and perhaps a book of essays, but I'm thinking of looking into something like the Foreign Service. I'd like to get back on the ground, in a space where language is manifestly urgent and exigent. It would be great to go back to Hong Kong, where I feel like I've committed myself to the issues there, but it would mean finding a way to go back without being swallowed by the city's many madnesses.

© 2024